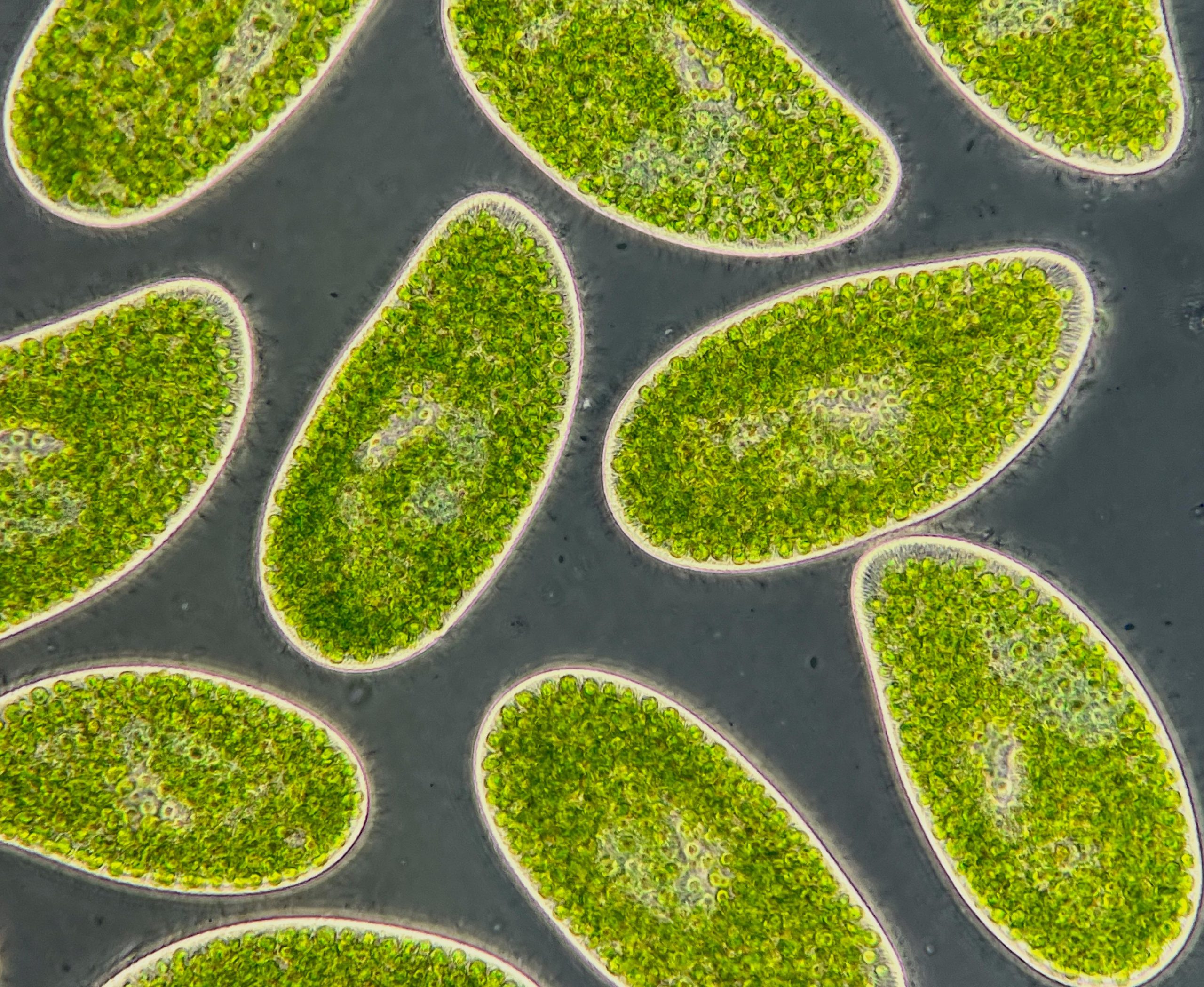

世界的に湖や川に見られるこれらの単細胞生物 Paramecium bursaria 食べて光合成ができます。 このような微生物は気候変動において二重の役割を果たします。 つまり、温暖化の主な原因である熱を閉じ込める温室効果ガスである二酸化炭素を放出または吸収します。 出典:Daniel J. Wieczynski、デューク大学

熱レベルが高くなると、海洋プランクトンや他の単細胞生物が炭素しきい値に向かって移動し、地球温暖化を悪化させる可能性があります。 しかし、最近の研究では、これらの生物が臨界点に達する前に早期警告信号を識別することが可能である可能性がある。

広範囲で頻繁に見落とされる微生物の種類を研究する科学者のグループが、地球温暖化を深めることができる気候フィードバックループを発見しました。 しかし、この発見は銀色の裏地が付属しています。 早期警告信号かもしれません。

コンピュータシミュレーションを活用して、デューク大学とカリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラの研究者たちは、湖、泥炭地、その他の生態系に生息する多数の単細胞生物と一緒に、世界中の海洋プランクトンの大部分がティッピングポイントに到達できることを証明しました。 ここで二酸化炭素を吸収する代わりに、彼らはその逆の仕事を始めます。 この変化は、代謝が温暖化に反応する方法の結果です。

二酸化炭素は温室効果ガスであるため、温度をさらに上げることができます。 少量の温暖化が、大きな影響を与える暴走の変化につながる可能性がある肯定的なフィードバックループです。

しかし、これらの生物の豊かさを注意深く監視することで、我々は6月1日にジャーナルで発表された研究で、ティッピングポイントがここに到達する前に期待できると報告しました。 機能エコロジー。

新しい研究では、研究者たちは、条件に応じて植物のように光合成したり、動物のように餌を狩ることができる2つの代謝モードを混在させるため、名前付き混合栄養生物(mixotrophs)と呼ばれる小さな生物のグループに焦点を当てました。

「彼らはまるで[{” attribute=””>Venus fly traps of the microbial world,” said first author Daniel Wieczynski, a postdoctoral associate at Duke.

During photosynthesis, they soak up carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas. And when they eat, they release carbon dioxide. These versatile organisms aren’t considered in most models of global warming, yet they play an important role in regulating climate, said senior author Jean P. Gibert of Duke.

Most of the plankton in the ocean — things like diatoms, dinoflagellates — are mixotrophs. They’re also common in lakes, peatlands, in damp soils, and beneath fallen leaves.

“If you were to go to the nearest pond or lake and scoop a cup of water and put it under a microscope, you’d likely find thousands or even millions of mixotrophic microbes swimming around,” Wieczynski said.

“Because mixotrophs can both capture and emit carbon dioxide, they’re like ‘switches’ that could either help reduce climate change or make it worse,” said co-author Holly Moeller, an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

To understand how these impacts might scale up, the researchers developed a mathematical model to predict how mixotrophs might shift between different modes of metabolism as the climate continues to warm.

The researchers ran their models using a 4-degree span of temperatures, from 19 to 23 degrees Celsius (66-73 degrees Fahrenheit). Global temperatures are likely to surge 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels within the next five years, and are on pace to breach 2 to 4 degrees before the end of this century.

The analysis showed that the warmer it gets, the more mixotrophs rely on eating food rather than making their own via photosynthesis. As they do, they shift the balance between carbon in and carbon out.

The models suggest that, eventually, we could see these microbes reach a tipping point — a threshold beyond which they suddenly flip from carbon sink to carbon source, having a net warming effect instead of a cooling one.

This tipping point is hard to undo. Once they cross that threshold, it would take significant cooling — more than one degree Celsius — to restore their cooling effects, the findings suggest.

But it’s not all bad news, the researchers said. Their results also suggest that it may be possible to spot these shifts in advance, if we watch out for changes in mixotroph abundance over time.

“Right before a tipping point, their abundances suddenly start to fluctuate wildly,” Wieczynski said. “If you went out in nature and you saw a sudden change from relatively steady abundances to rapid fluctuations, you would know it’s coming.”

Whether the early warning signal is detectable, however, may depend on another key factor revealed by the study: nutrient pollution.

Discharges from wastewater treatment facilities and runoff from farms and lawns laced with chemical fertilizers and animal waste can send nutrients like nitrate and phosphate into lakes and streams and coastal waters.

When Wieczynski and his colleagues included higher amounts of such nutrients in their models, they found that the range of temperatures over which the telltale fluctuations occur starts to shrink until eventually the signal disappears and the tipping point arrives with no apparent warning.

The predictions of the model still need to be verified with real-world observations, but they “highlight the value of investing in early detection,” Moeller said.

“Tipping points can be short-lived, and thus hard to catch,” Gibert said. “This paper provides us with a search image, something to look out for, and makes those tipping points — as fleeting as they may be — more likely to be found.”

Reference: “Mixotrophic microbes create carbon tipping points under warming” by Daniel J. Wieczynski, Holly V. Moeller and Jean P. Gibert, 31 May 2023, Functional Ecology.

DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14350

The study was funded by the Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy.

![[JAPAN SPORTS NOTEBOOK] 西岡吉仁、初フランスオープン4回転進出 [JAPAN SPORTS NOTEBOOK] 西岡吉仁、初フランスオープン4回転進出](https://japan-forward.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Nishioka-JF-0604-1000x600.jpg)

+ There are no comments

Add yours